A TODO TREN: THE ALMERIA – LINARES LINE

100 Years of Almerian Railways

By Antonio Aguilera and Domingo Cuéllar

Foreword

In October 1999, the Friends of Almerian Railways (ASAFAL) held an exhibition to celebrate the centenary of railways in the province of Almería. To go with this exhibition they produced a book, “A Todo Tren” which may be translated as “The train for everyone”. This (Spanish) book contains chapters on the history and development of the railway, particularly on the Almería to Linares line. I have translated this history plus some other items of relevance into English. I have not included a few items in the book such as railway stamps and railway models. The Introduction and Prologue have been edited and changed from present to past tense.

The pictures on this page, and the gallery at the end may be expanded by hovering the curser over them. They use the clever piece of code by Scott Kimmler of randsco.com, whom I acknowledge here,

Acknowledgements

My thanks to ASAFAL for permission to publish this translation on to my web site, and to John Hearfield and Gerald Strowbridge for proof reading the article.

Contents

Click on a chapter to go straight to it

- Introduction

- Prologue

- Waiting for the train

- The projects and construction of the railway

- The South of Spain Railway Company

- The Mining Companies and the Railway

- Development of the line

- From steam to TALGO

- Coaches and Wagons

- Passenger Trains

- The Human Factor

- The Future

- Gallery of Pictures

Introduction

The railway, its history, its world and the things associated with it have always received special attention both from researchers and aficionados. The railway brought a spectacular advance in the development of transport in the 19th century.

Its arrival in Almería was delayed for some decades compared to the rest of Spain and Europe, so it was in 1999 that we commemorated the construction of the railway line from Linares to Almería which finally allowed us to join the civilised world. ASAFAL and the Almería Institute organised an exhibition, of which this publication tries to give a general overview.

In this exhibition, we not only made a journey through history and the technical development of the railway, we paid homage to the men and women who lived and worked on and for them.

Antonio Aguilera and Domingo Cuéllar Villar

Prologue

A commemorative exhibition not only has to show and record, so that its visitors value what has been done by others in the past, but also to encourage them to think what might be undertaken in the future.

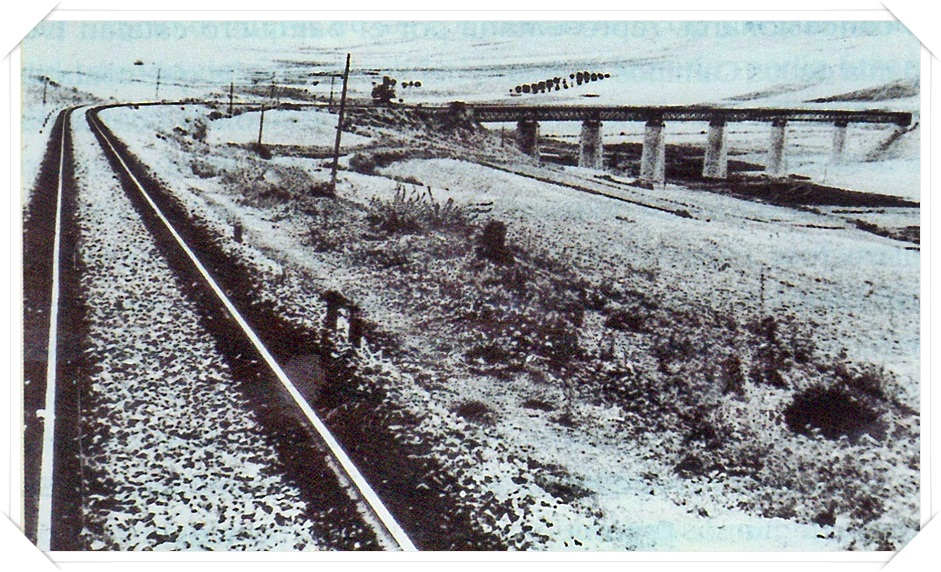

The first time I travelled from Madrid to Almería I went by train. I remember the various landscapes that I passed through left an impression on me. There were stretches of land that seemed like a lunar landscape, the Penibetica mountain range, the snow so close that you could almost reach out and touch it, and the almost dry valleys, particularly the River Andarax. But above all the impression was of bridges and viaducts, and the beauty of the station when I arrived. I remember thinking how difficult it must have been to build the line and how important it was for Almería to have contact with the rest of Spain.

When I made that journey I knew little of the line and its history, but I was aware overall how important the railway was in transforming social and economic life. I also knew, although only in a general way, the value represented by enormous technical, economic and human effort that had been needed for the construction of the line across a tortuous countryside full of problems.

Rafael Ruiz Sanchidrián, Director of Museum Management FFE

1. Waiting for the Train

At the beginning of 1870, in an area without railways, such as Almería, the investment in public works centred on the modernisation of the road network. The State roads provided undoubtedly the majority of communications in the province, alleviating in some way its isolation.

In the period 1850 - 1900 the central administration constructed a total of 595 km of roads in the province. This was the only means of communication to the interior. These primitive roads, with steep hills and tight bends required important construction work - bridges, viaducts etc. They were surfaced with tarmacadam, in a process that consisted basically of layers of crushed rock of different size, compacted with a heavy roller and topped with a fine layer of gravel or sand and rock.

The need for a railway was imperative at this time, particularly since the rest of Spain already had them. In 1885 only Teruel, Soria and Almería had none. Everywhere else enjoyed the benefits of a railway system; the enlargement and diversification of internal markets, a dynamic demographic interest and the development of activities relating to primary materials in proximity to a railway.

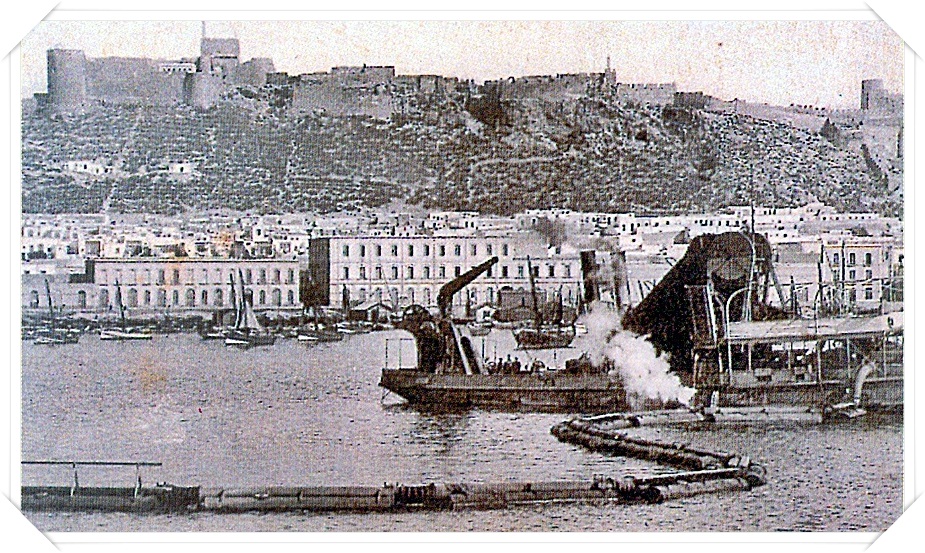

The road and rail transport routes were completed with the construction of ports. In Almería it was mostly primary materials such as minerals, esparto, barrels and grapes that were exported. These required adequate protection when loading, particularly for large capacity ships. Improvements continued throughout the first third of the 20th century and were given a boost by the completion of the Linares-Almería railway.

In the Province, the bays of Adra, Roquetas, Garrucha and Villaricos also received an important construction boost. This was due to the export of minerals and esparto. In a geographical area like Almería with obvious difficulties in moving across the interior, sea transport was the obvious export solution.

The Almerian press pushed for the railway with a popular outcry and continued the pressure until it was agreed to auction a concession. The main arguments used were economic, particularly relating to the mining areas of the Sierra Nevada and Los Filabres. The need to alleviate its isolation and introduce a railway required a complete change of direction for the Almerian economy. Also one needs to stress the affront felt by Almería at being disadvantaged compared to the rest of the country.

2. The projects and construction of the railway

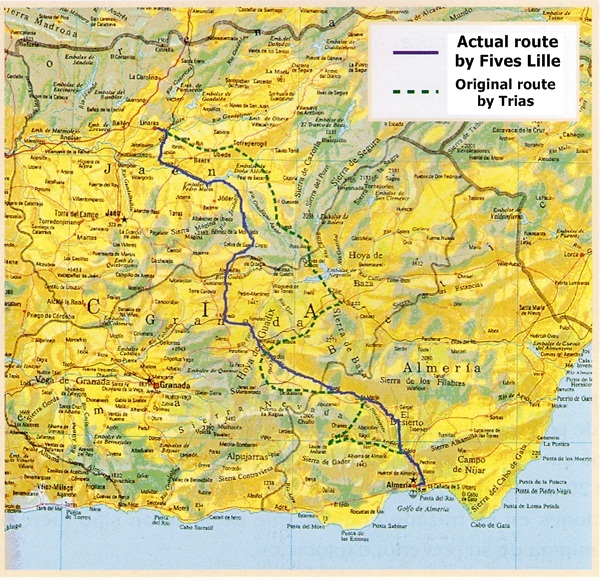

Click on the map for an enlargement

Starting in July 1873 and under the auspices of the Provincial council of Almería, the engineer José Trías Herráiz began studies on a line which would connect the mining town of Linares to Almería. He also tried with this plan to connect remote areas to the railway. He wanted to link the port to the lead mines of Sierra Morena and the commercialisation of the timber from Sierra de Segura for export. Trias designed a line of 305 Km that connected Linares, Baeza, Úbeda ,Baza, Guadix, Fiñana, Laujar, Alhama de Almería, Gádor and Almería (dotted green line on the map above).

The project, approved in 1875 by the ministry with the important agreement of local politicians, did not find favour with investors, who doubted its viability. There would follow 20 long years before the appearance of the railway, with significant changes to the original plan, to take into account the effect of mining in its later development.

The concession could only be won if the interests of the mining companies and the possibility of modifying the plan could be met. Effectively the adjudication promulgated on 18th May 1889 modified the line in accordance with these wishes.

The main alterations were made by the company Fives Lille in 1893. These alterations meant the bypassing of the Alto Andarax valley, the towns of Marquesado del Zenete and Baza and its environs, and the prosperous townships of Loma de Ubeda. In short the railway crossed an “authentic population desert" (solid blue line on the map above).

The concessionary company, represented by the Catalan banker Ivo Bosch, was the “South of Spain Railway Company (SSRC)" that was financed primarily as a Franco-Belgian concern. This contract with the French company Fives Lille was for a little over 80 million pesetas (or francs since there was parity at that time). This company originally specialised in manufacturing for the sugar industry but had diversified into railway construction and steam engine manufacture. Right from the beginning there were arguments between the two companies. As a result Fives Lille did not complete construction in the allotted time (4 years for the handing over of the line with all fixed installations and mobile material complete). There were thus great financial problems for the SSRC who suspended payments in 1895 until work had been finished.

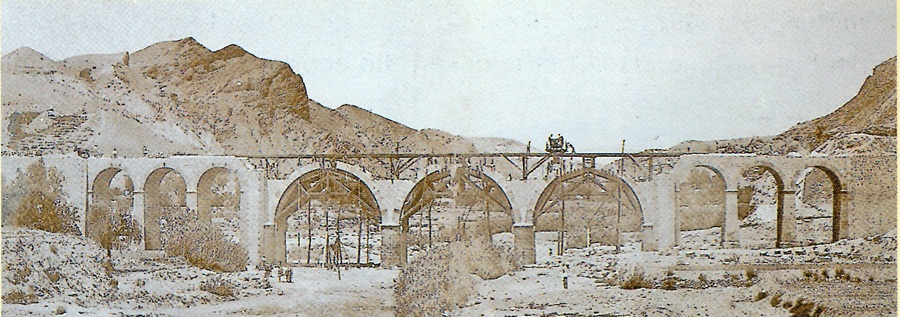

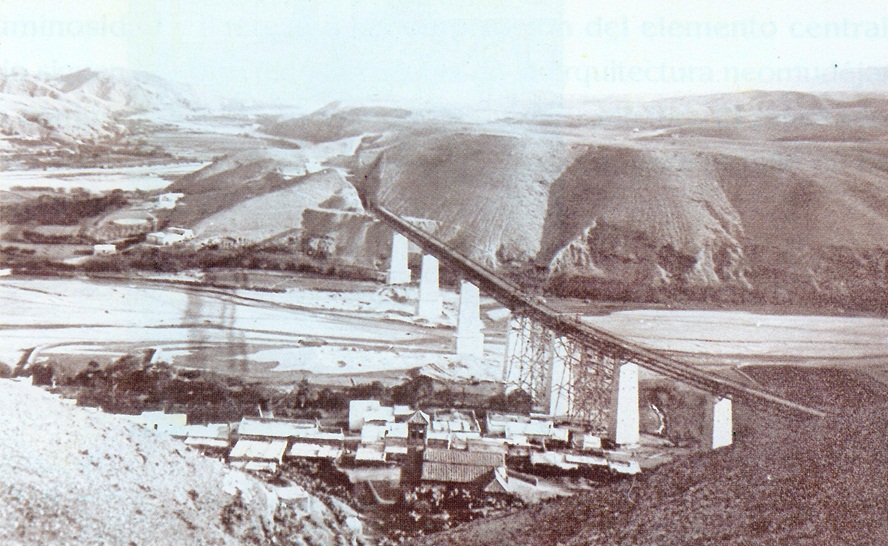

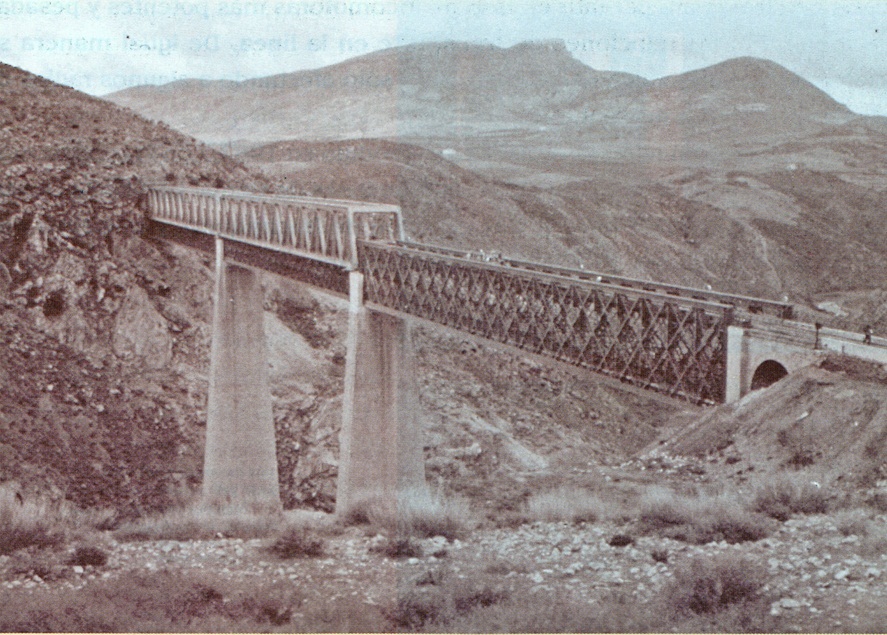

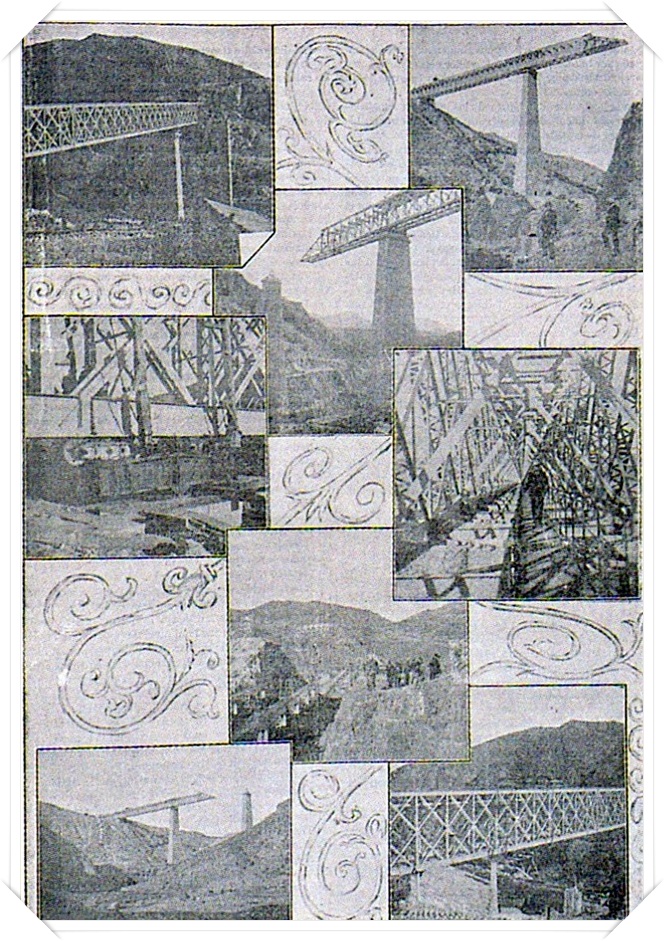

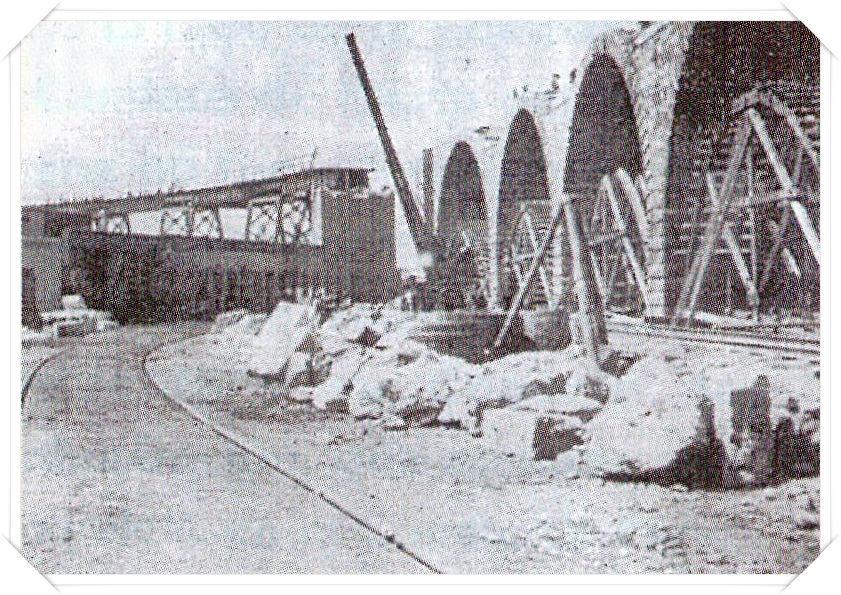

The Linares- Almería line would prove to be one of the most costly in the Spanish network. The enormous difficulties in overcoming the mountain terrain really showed itself in the quantity of tunnels and bridges, the like of which had not been seen before. Examples are the impressive viaducts, such as the one at Santa Fe over the Andarax River, or at Alamedilla which at 625 metres was the longest at the time. However, without doubt the most famous was the viaduct at Salado, over its Arroyo. This was in Jaen Province and had metal sections 105 metres long, and was more than 100 metres high over the bed of the arroyo. The enormous technical problems attracted many experts of the time. It also featured in a special report for the Magazine of Public Works in Madrid. Its completion has linked Almería with Madrid for over 100 years.

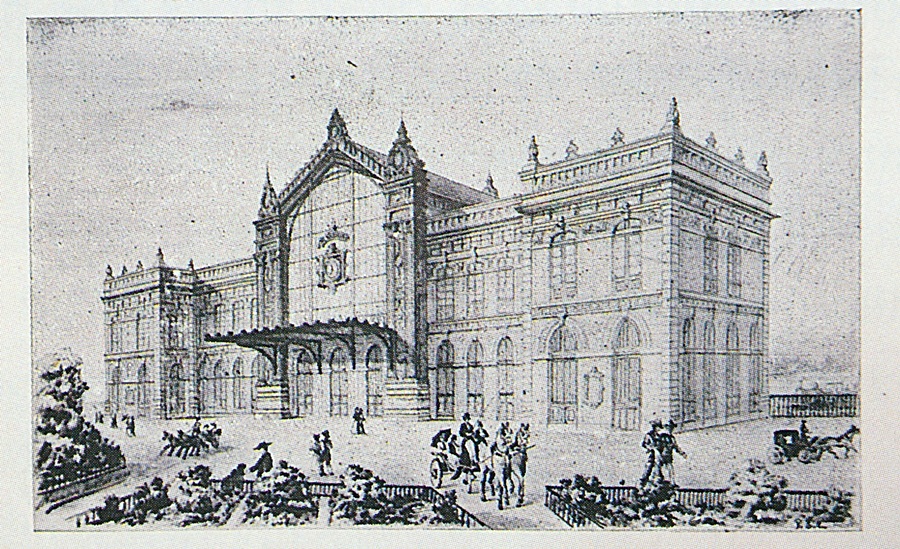

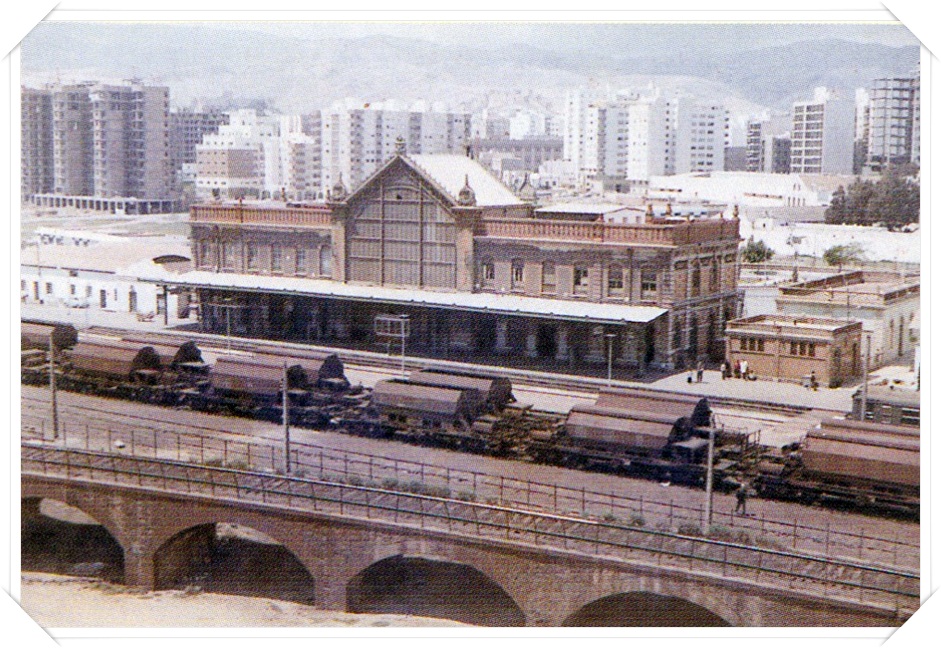

Almería station is one of the important cultural and historical legacies of the city. Framed in the historical scene of the 19th century its construction combines the typical architectural elements of cast iron and glass that brings brightness and light to the composition of the central elements. The halls cross to the other side with classic neomudejar lines*, thus making a link between modernity and tradition. The result without doubt is an admirable architectural expression that remains as a thing of pride for Almería with its splendour remaining today.

*Mudejar is an architectural style is that based on a mixture of Christian and Arabic techniques.

For more pictures of the construction, go to the Gallery of Pictures

3. The South of Spain Railway Company

Note. This was a different company from the Great Southern of Spain Railway

The SSRC was created on 26th June 1889 in Madrid with the aim of developing the Linares- Almería line that had been granted its concession on l8th May that year.

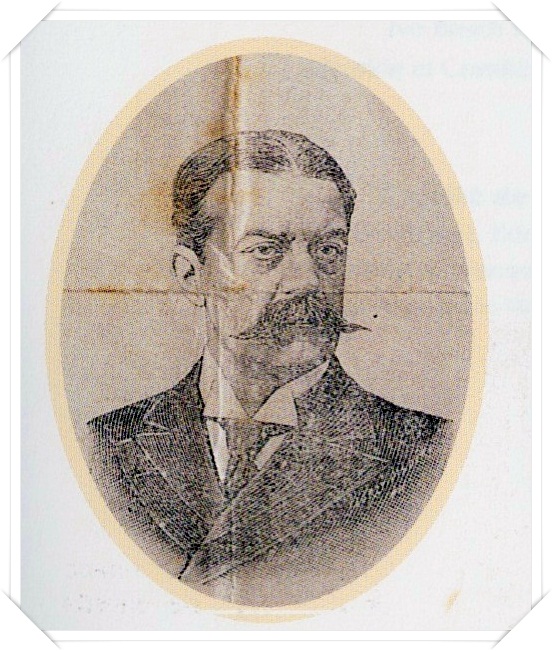

The only applicant for the grant was the Banco General de Madrid, whose president, Ivo Bosch Puig (1852-1915) was the prime promoter of railways in this part of Spain. He was an expert in negotiating the rescue of bankrupt banks - such as the Credit Mobilier in 1880 or the Societé Inmobilier - both of whom had considerable involvement in places as far apart as Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Colombia and France. He was also part of the administration of companies as diverse as the Madrid Telephone Company, the Sociedad Inmobilier of San Sebastian, and the Submarine Cable Company.

He was determined to acquire the concession for the Almeria-Linares line and always believed in the profitability of it.

Railway negotiation in Spain was undertaken on the basis of private management and development. Concessions for a particular length of line were put up for public auction. They lasted for a stipulated time - usually 99 years. Under State supervision the successful company had to comply with a number of conditions such as a limit on tariffs, amount of rolling stock, stations provided etc.

For finance, the companies relied on three main sources of income.

(a) The sale of company shares

(b) Debentures

(c) Government grants. These were given to cover areas with particular difficulty in construction

In the case of the SSRC, as with much of the rest of Spanish Railways, the majority of shareholders were from France and Belgium, although there was also an important group of Catalan capitalists, associates of Bosch. There were also a number of small investors from the south east like the Almerian deputies José Cárdenas and Antonio Navarro, the Almerian company Spencer and Roda, the Almerian Council and the local banker González Canet.

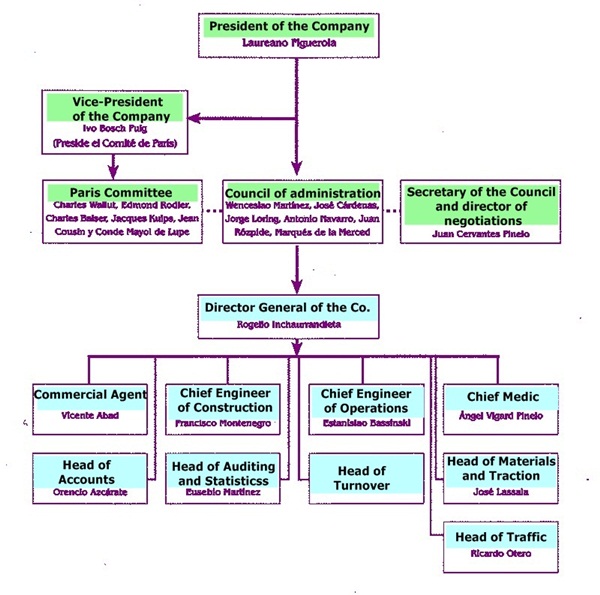

The structure of a railway company in the 19th century followed the pattern set by North American companies of that time. On one side was the administration council who ran the financial side of things and on the other were the teams and technicians who actually ran things. The situation with the SSRC is shown here.

At the head were the president and his administration council. They worked in parallel with the Paris committee, justified by the importance of foreign investment. For operations there was a director- general who was in charge of the management of the various services; development, ways and works, workshops, traction, accounts etc.

The poor economic results for the company meant that it was in trouble right from the start, and it ended up by being taken over, although much later, by the Andalusia Railway company on 29 June 1929. They paid 20,177,705.59 pesetas, and included it as part of the Western Andalusia line. In 1941 everything was nationalised under RENFE.

4. The Mining Companies and the Railway

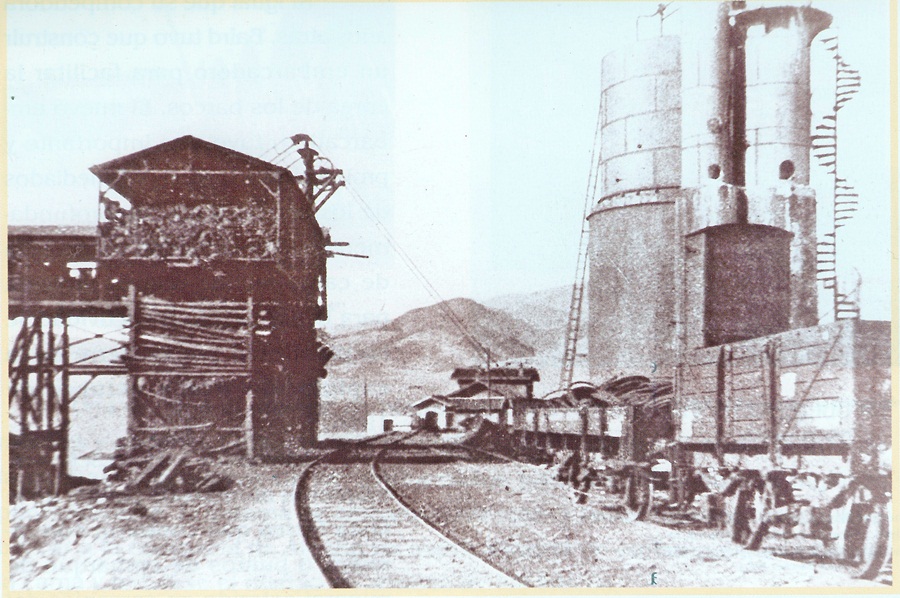

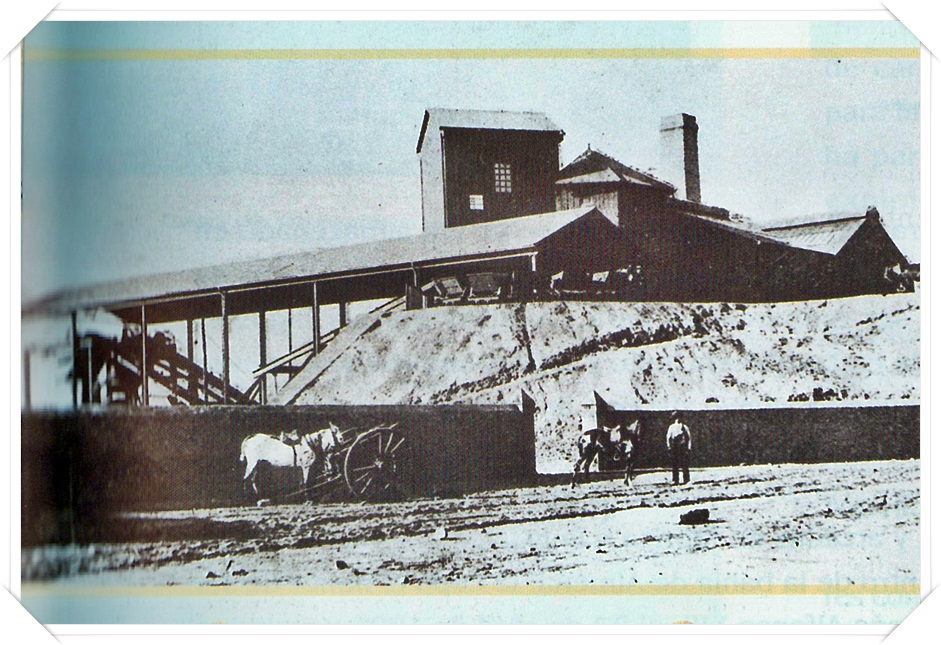

Once the first few kilometres were in place, the mining companies began to consider linking their mines to the railway. One of the first to do so was the Alquife mine. It constructed a line to link the deposits situated in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada to the line at La Calahorra and Ferreira. This branch, which was for commercial traffic only, commenced service on 27th December 1899 and operated continuously until 1973 when the mine closed.

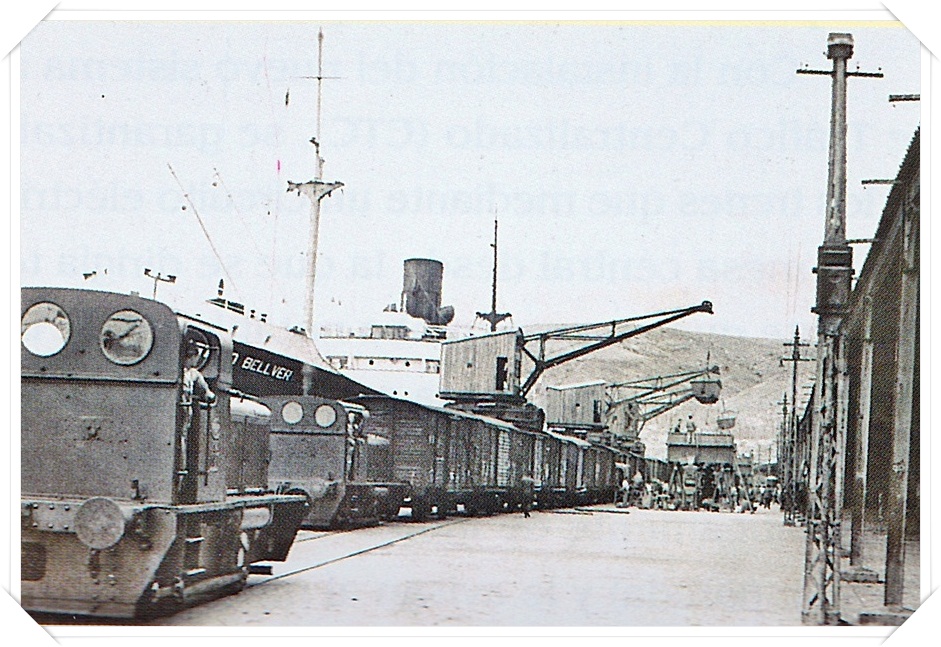

Once the iron ore arrived at the port it was stored in moles or at platforms near the railway station. There it waited to be shipped to blast furnaces, mostly in England. The loading of ships was slow and uneconomical and the company searched for a better way which would ease loading and reduce the mooring times for ships.

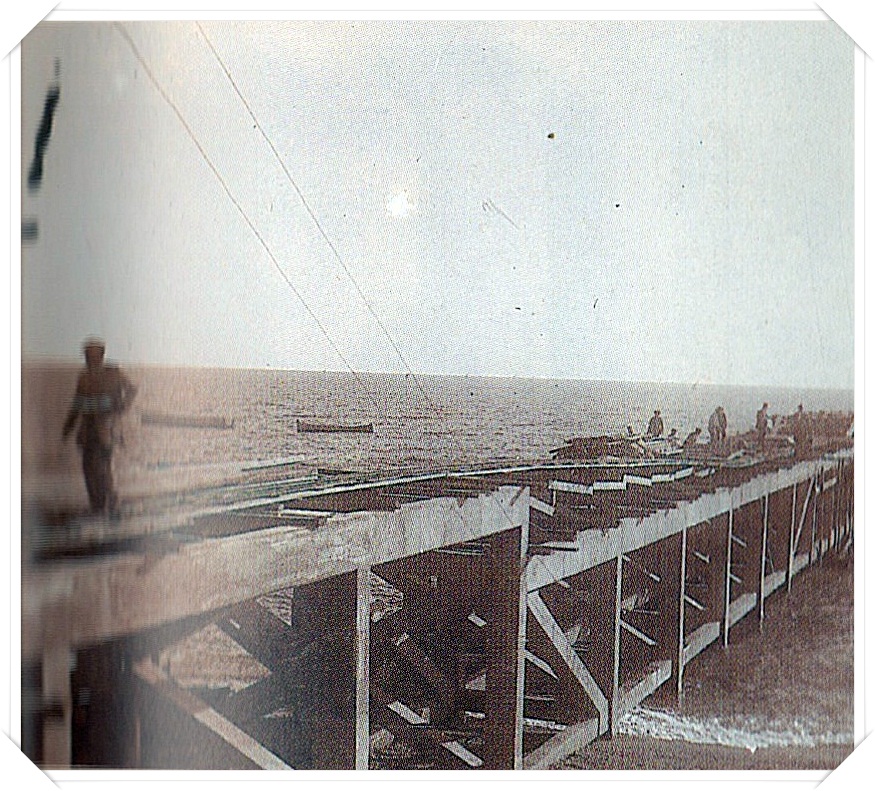

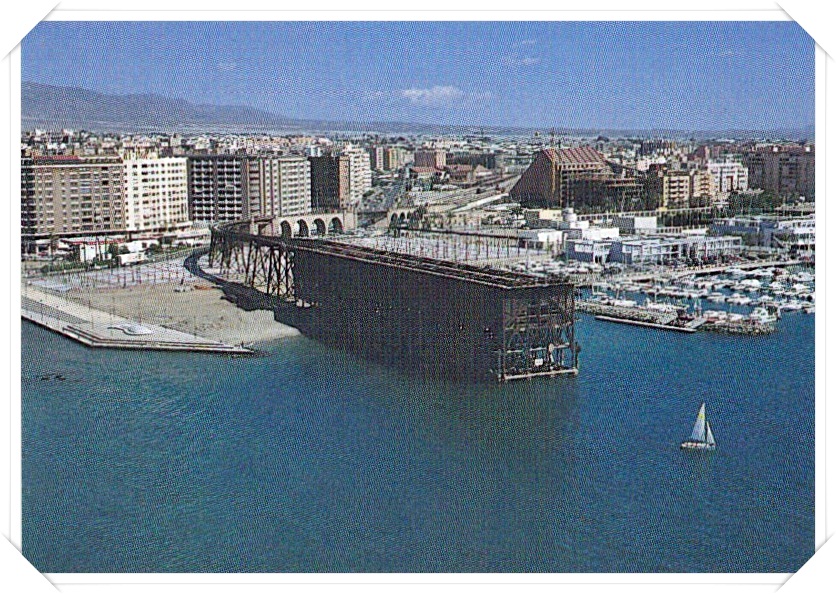

To this end, they built between 1902 and 1904 a metal pier (EL Cable Ingles) with metal struts and arches from the port to the railway station. Located in Almería bay, it received the honour of being opened by the King of Spain, Alfonso 13th on 27th April 1904 and remained in service until the closure of the mines in 1973.

In 1998 it was designated a site of cultural significance and awaits its restoration. (Some work has now been done on this.)

In 1905, a new company was formed In the Alquife region, the Bairds' Mining Company. It also intended to transport iron ore to Almería. In tough competition with Alquife mines, William Baird needed to construct his own railway to link up with the Almería -Linares line. This went to Huéneja y Dólar station and opened on 20th September 1916. Like his competitor earlier, Baird also had to construct his own pier. This new pier had a long and active life and in the middle of the 70's was extensively modified to cause much less disturbance to the population. All activity ceased when operations closed in October 1996.

Further to the two companies described, there were numerous other points on the line where branches went off to collect minerals extracted from the neighbourhood of the railway.

La Société des Mines de Beires constructed an aerial cable from one of these points to the station of Doña María Ocaña on the railway in 1904. With little transport capability it had a poor return and the concern passed to the Soria Mining Company in 1907. This company continued until 1921.

Under the initiative of Thomas Morell, now that the railway was complete a normal gauge line was built between Gérgal and this station to facilitate the transporting of material which flowed via various aerial cables to the point known as Cruz de Mayo. The line went into service on 27th July 1901 and remained until 1930.

For more pictures of the mines, go to The mining companies

5. The development of the line

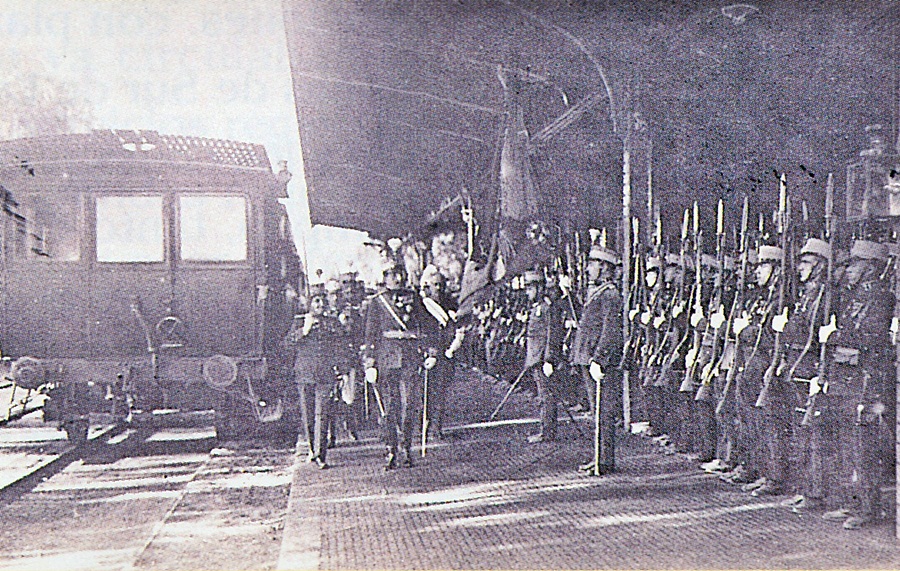

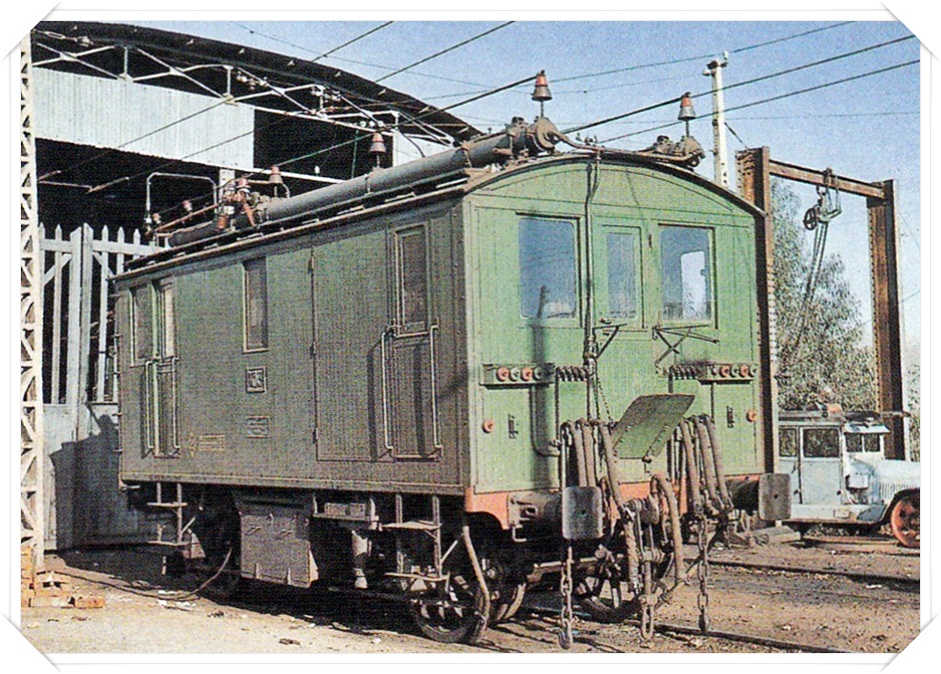

The first big milestone in the technical renovation of the line happened in February 1911, with the opening of what would be the first electrified line in Spain. This was between the Almerian stations Santa Fe Alhama and Gérgal. An electric feeder ran along the length of this 22km route, which covered the steepest section of the line with an average gradient of 1:37. The frequency was 25Hz at 6kv. The electricity was generated at a power station near Santa Fe de Mondújar on the banks of the Andarax. Today one can still see its imposing chimney among the orange groves that surround the town.

The electrification and the engines that ran on the line were built and supplied by the Swiss firm Brown-Boveri. They initially supplied five engines (Nos. 1-5). Much later, when electrification was extended between Gádor and Nacimiento, two more were added.

To see how this system worked, select this link ThreePhase Page

The object of this improved technology was to optimise the transport of minerals, the main traffic on the line. This would improve speeds and capacity of all types of loads, thus attempting to avoid bottlenecks and their consequent negative effect on the mining companies.

The new system was designed solely for goods traffic, and had priority over passenger services. Heavy loads placed a great strain on a line with such steep gradients and so many hills and valleys, bridges and sharp bends. As a result, there was considerable wear and tear on the line. A poor level of re-investment exacerbated the deterioration of the rails and crossings, plus the general maintenance required on a railway. The result was a line in a deplorable condition. The civil war made things worse. (For a brief description of the war and how it affected Almeria, see pages 20-22 of my book. For a full description, try The Spanish Civil war by Hugh Thomas, ISBN number 0-14-020970 0.)

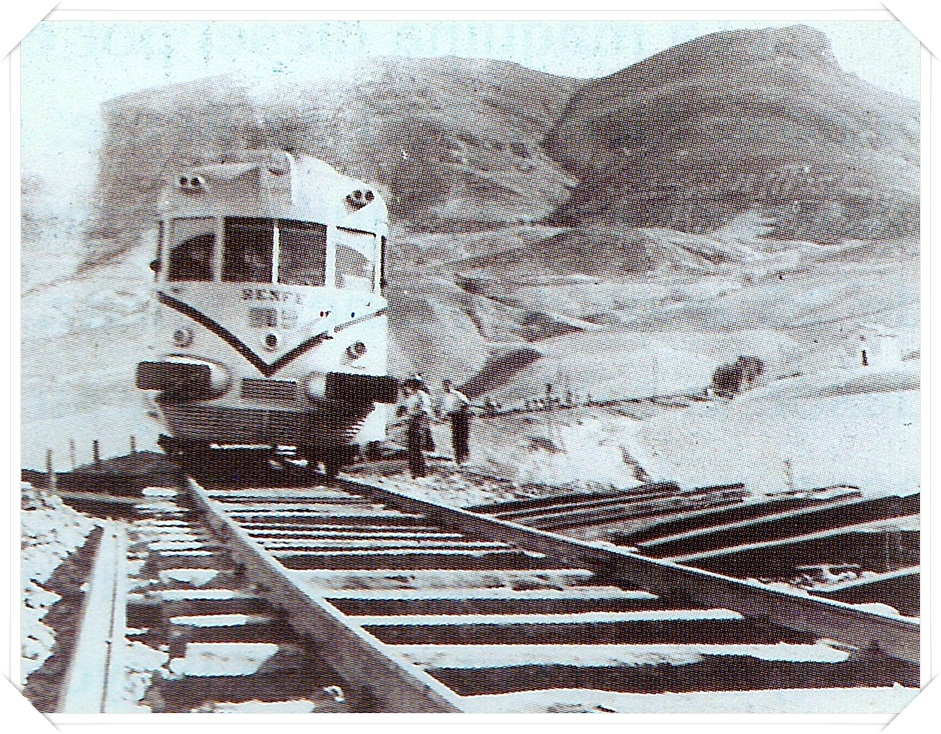

But there was hope. Small and limited improvements occurred, until in the 70s RENFE faced up to a complete renovation of the line. This included a total change of track, crossings and ballast. At the same time they replaced the major metal bridges - Guadalimar, Salado, Hacho, Victoria and Andarax by bridges made from pre-stressed concrete. Some were made of steel to permit the passage of heavier and faster trains, improving facilities. There were slight alterations to the line but only in order to smooth out some of the bends. The picture is of the renovation of the metal at s

The last major improvement took place in 1987. 7 krn of new track between Gérgal and Doña María-Ocaña were built to by-pass the difficult pass at Nacimiento. It cost 1,000,000,000 pesetas (approx £400,000).

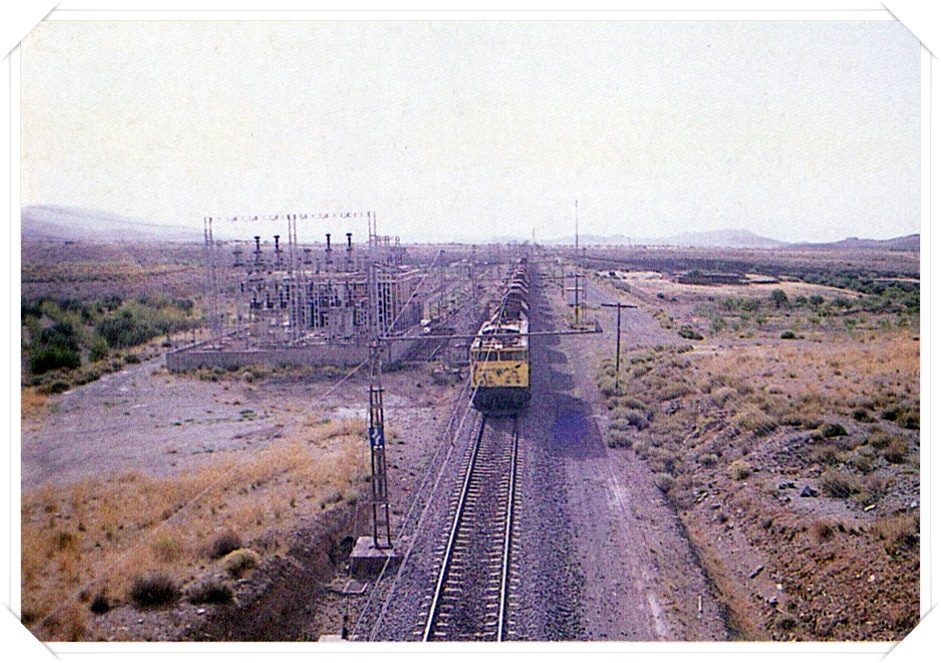

In the 80's, RENFE decided to provide a new electric system to improve mineral transport. By now this came exclusively from the Andalusia Mining Company at the Marquesada mines - the old deposits at Bairds.

Seventy years on, history had repeated itself. We had an island of electrical traction in the Almerian network, solely for mineral transport, with no connection to the outside.

The system chosen was the normal Spanish feeder of a single wire of 3,300 VDC. It was distributed via substations and taken from two locations of the Electricity Company of Seville. One was at Atarfe (Granada) and the other at Benahadux (Almería).

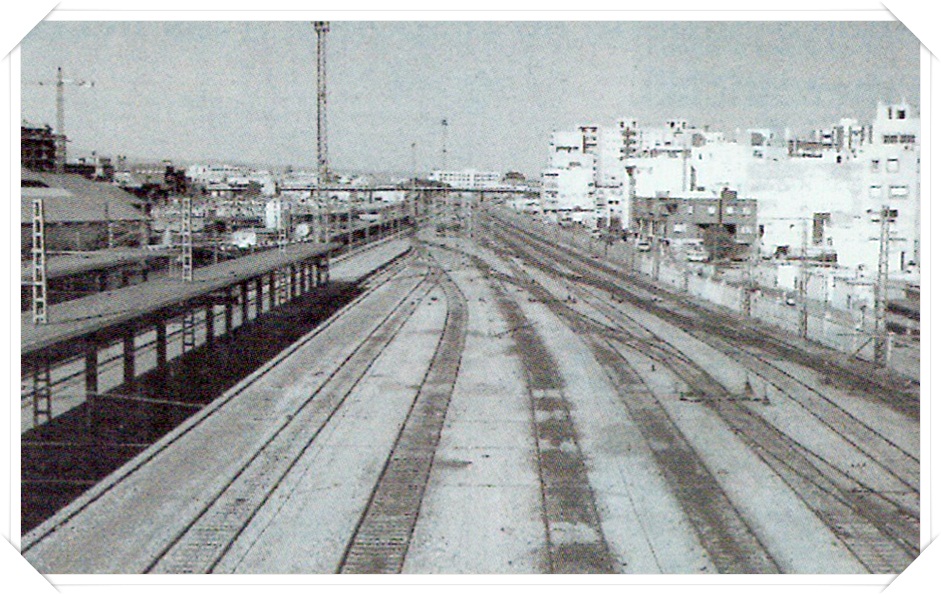

Once the closure of the mines became an established fact, the objective had to be to correct the isolation of Almerian electrification. This would allow a substantial improvement in various parts of the Linares - Almería and Moreda-Granada lines. There would be engines and other rolling stock of modern construction which would optimise travelling times and quality of service.

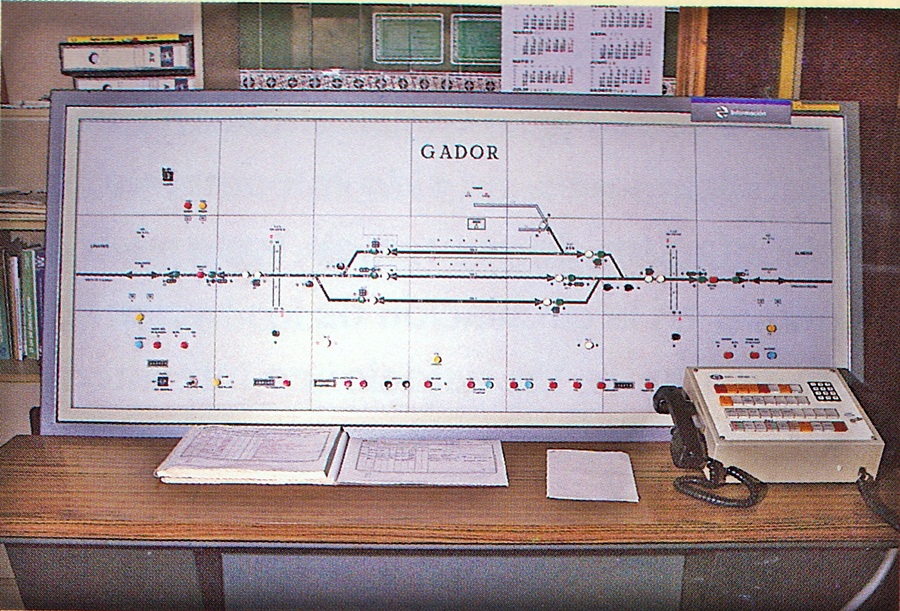

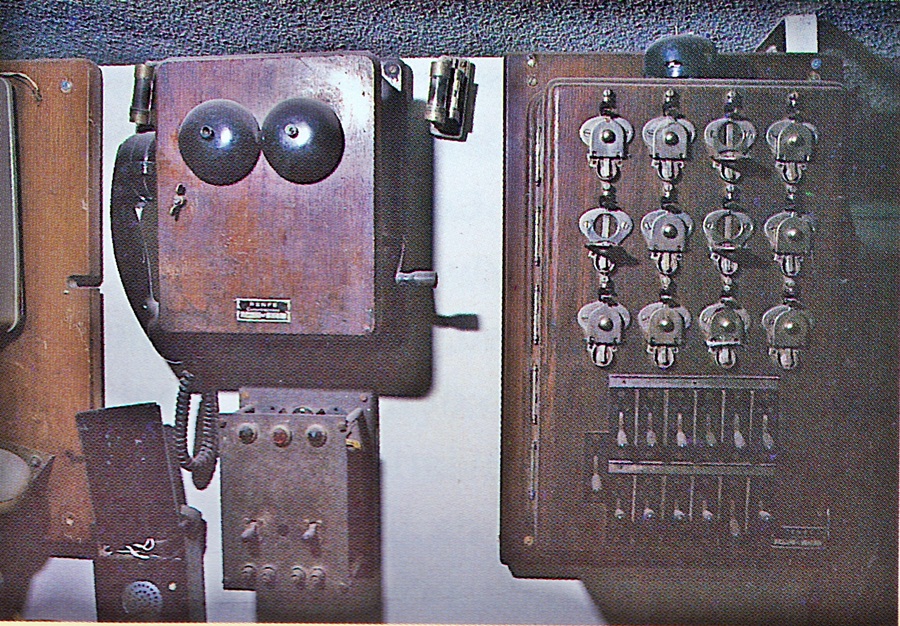

The last big modernisation on the line and the most innovative was a complete replacement of traffic control. Up to 1991 the security of trains was done telephonically. Each station informed the next one of the situation on that section. This system, known as Telephone Blocking had a number of problems, both of security and delays.

The new automatic system, called Central Traffic Control, receives signals from all trains on the line. Then all traffic is controlled centrally, improving movement and reducing congestion. With the new system came an advanced set of traffic lights. These replaced the old mechanical semaphore signals.The lights change automatically to signal movement (way clear, precaution, warning of stop, stop), advising the driver of the situation ahead. Further, there is now direct communication between central control and all drivers. This was completed a short while later with the installation of the Signal Announcement and Automatic Braking system.

From the very beginning it was considered necessary to link Almería station with its port. In 1898, this connection was supplied. At first it was temporary, until the completion of the eastern mole and the coastal platform. This allowed continuity for export items such as minerals, grapes and esparto, and reduced transport costs.

The connection was kept, but badly maintained until 1925 when a new rail link was built. This link remained until fairly recently, allowing a rich interchange of merchandise.

6. From steam to TALGO*

*TALGO means Tren Articulado Ligero Goicoechea-Oriol (Articulated Light Train of Goicoechea-Oriol). Goicoechea (a Basque) and Oriol were the designers in 1941 of this speedy train that has seen many incarnations since.

There are too many pictures to fit into this chapter, so they are included as a gallery of locomotives at the end of this document.

The use of steam, produced by heating water by burning coal, wood or fuel oil, to produce movement, allowed the development of the railways in the early 19th century. Steam engines remained the major source of traction until their replacement by diesel or electric in the 1950s.

A steam engine is specially designed for the work it is to carry out. There are engines for high-speed passenger links, heavy goods towing, shunting duties etc. Thus there are many types of engines which are distinguished by their axle configuration. For example, an engine with two front axles, three linked driving axles and a single rear axle is called a "Pacific".

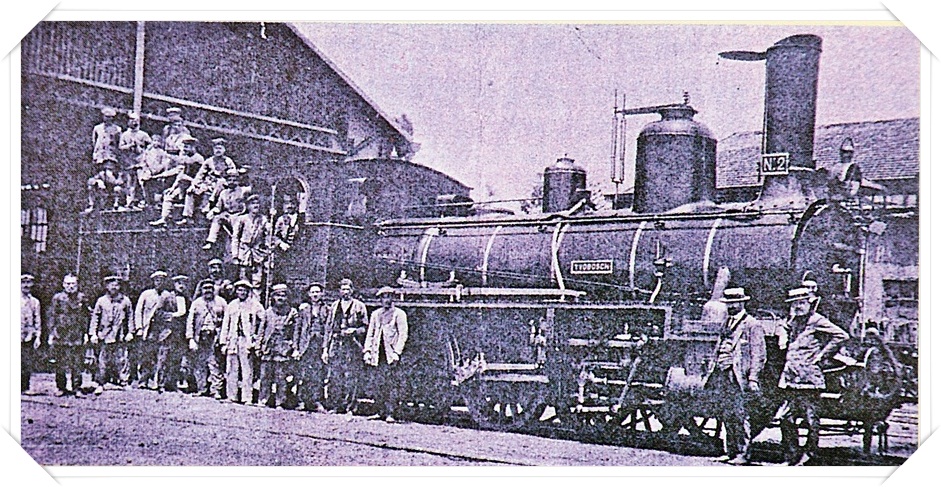

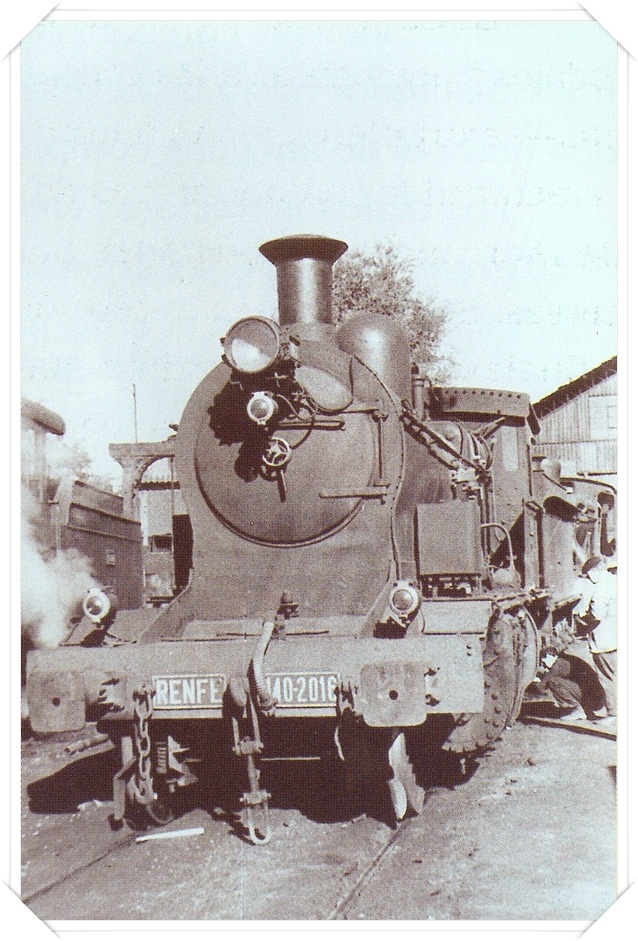

The SSRC owned from the beginning, locos of type 0-6-0 and 0-8-0 built by Fives Lille, the same company who built the line. They were general purpose machines with wheels of 1.6 metres diameter. These were suitable for climbing steep inclines on the line. Engine No 1 was named FIGUEROLA and No 2 IVO BOSCH. This was in honour of the main architects of the line. It followed a tradition, not pursued by RENFE, of naming engines after famous people, towns, monuments or geographical sites.

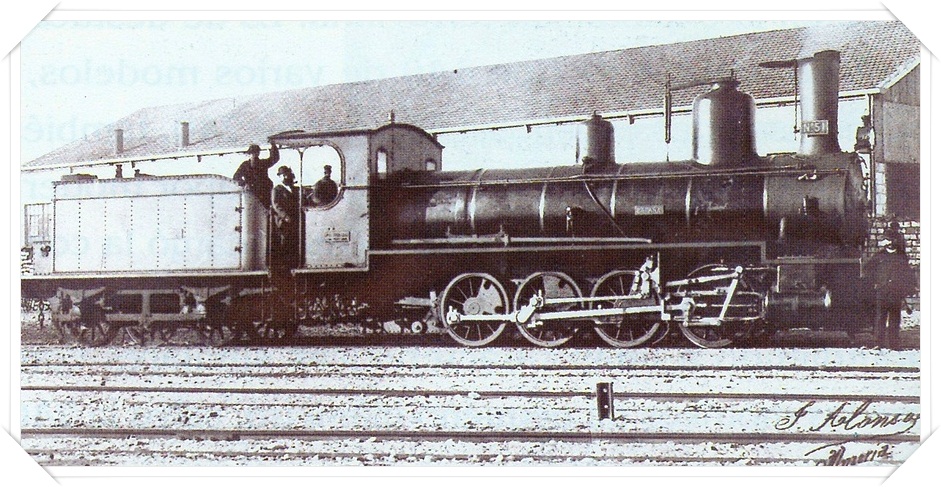

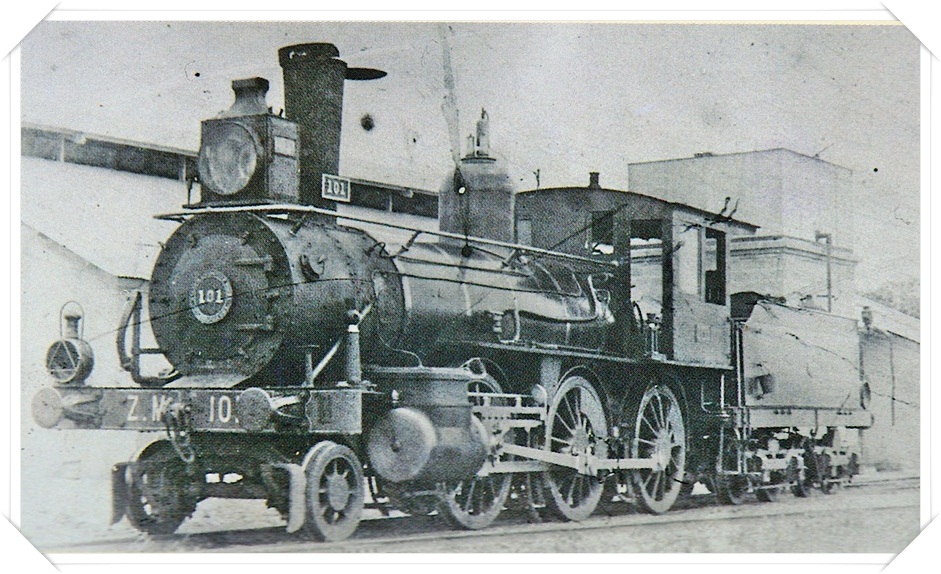

The SSRC purchased engines of varying wheel configuration and power. These came from a number of companies: Fives Lille, Krauss, Baldwin, Euskalduna etc. Some were foreign, some Spanish. Some were new, some second hand. All, however, had one characteristic – small driving wheels to cope with goods traffic, steep inclines and sharp bends. There was just one exception. These were 4-6-0 engines from Euskalduna at the end of the 1920's. These had a driving wheel diameter of 1.62mm allowing higher speeds on the passenger routes that they were assigned to.

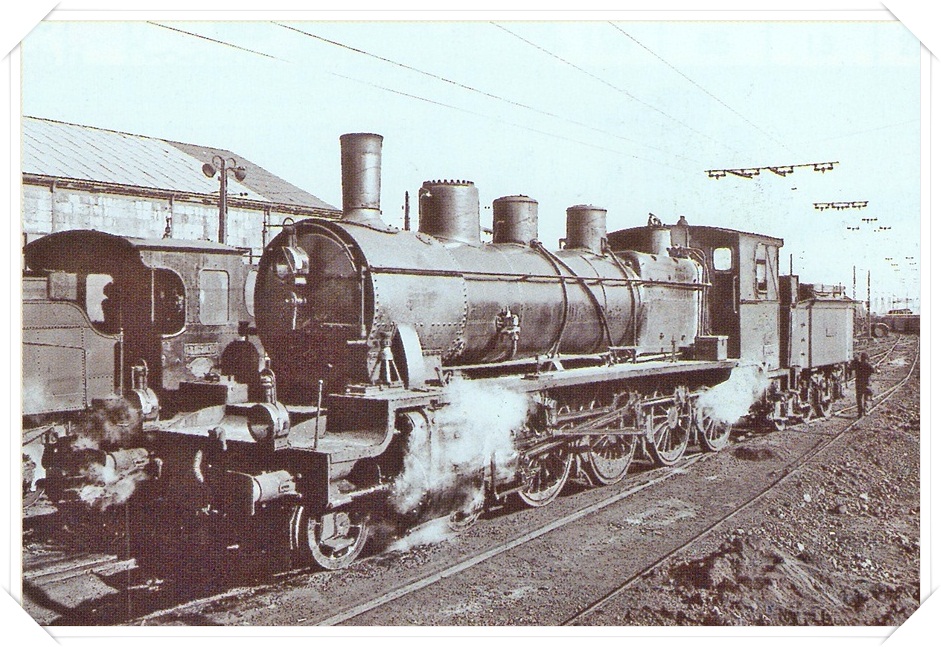

When the Andalusia Railways took over the line they introduced improvements in the traction which had been a weakness up to that point. The two introductions which stand out are the 2-8-0 locomotives of varying types, as well as the first of a Spanish series, the 4-8-0 "Mastodon" which then formed the base of modern steam traction.

The Andalusia Railway entrusted the manufacture of their engines to various companies, American, European and Spanish. All except the 4-8-0 had similar characteristics - low weight per axle and small diameter driving wheels. Again, this was due to the predominance of goods traffic on the line.

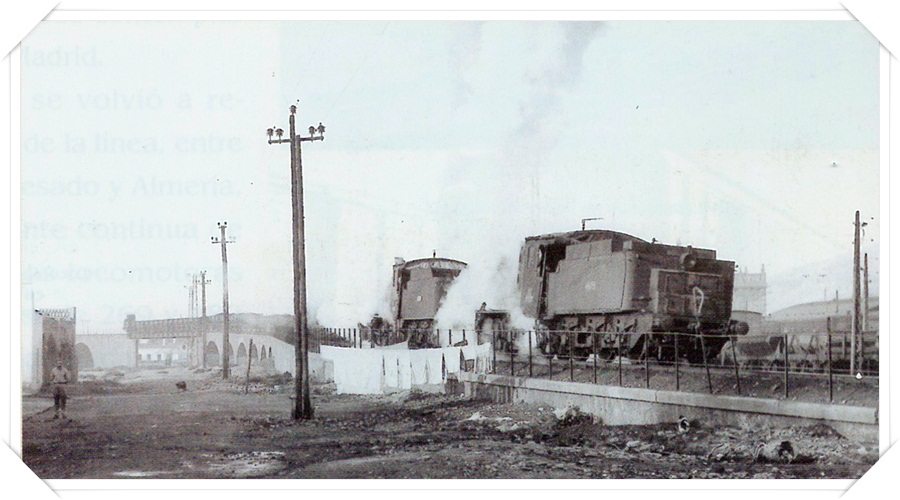

Under RENFE the lines were organised much as before, until dieselisation in 1966 when locomotives of other private companies such as MZA and the Western Railways started to appear.

The curious 3-phase electric engines, which appeared in 1911 between Santa Fe and Gérgal, were a definite aid to goods traffic on this difficult stretch. They normally travelled in coupled pairs and had two fixed speeds of 12.5 or 25 km per hour. The motors also acted as brake generators, feeding energy back into the line. They remained in service for sixty years. Of the seven units, No 3 survives in the Madrid Railway Museum.

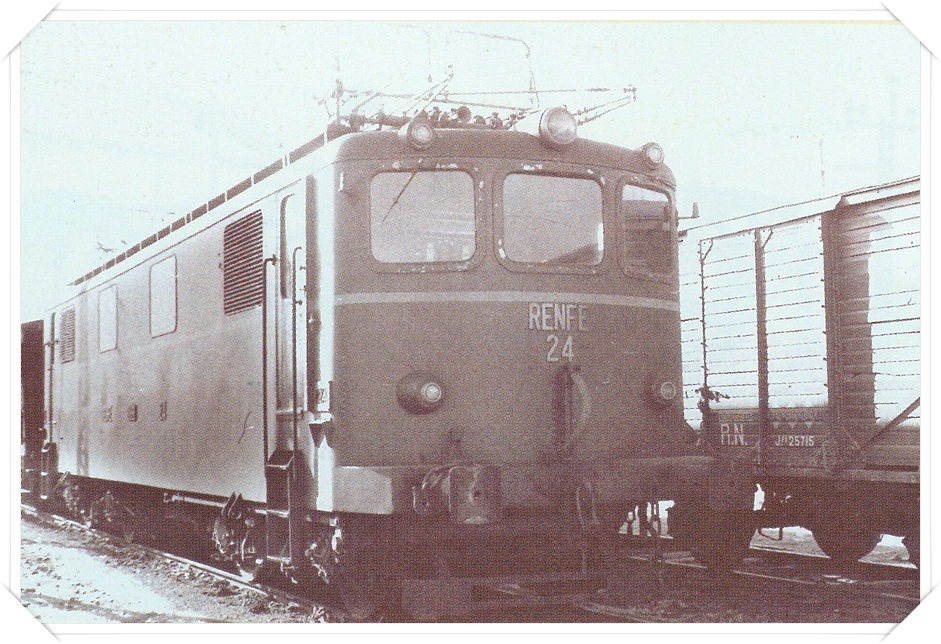

When electrification was extended to between Almería and Nacimiento, four more units were purchased (type Secheron). Although also 3-phase, they looked completely different. They had only a very short life of four years. No 22 can also be seen at Madrid.

In 1989 the line between Almería and the Marquesado Mines was re-electrified, this time with 3,300 VDC. Electric motors series 269 and 289 were nothing like their predecessors. Of Japanese design, they were very powerful with great traction capabilities. They were able to tow trains of more than 2,000 metric tonnes in double header. They were withdrawn at the end of 1996 when mining finished.

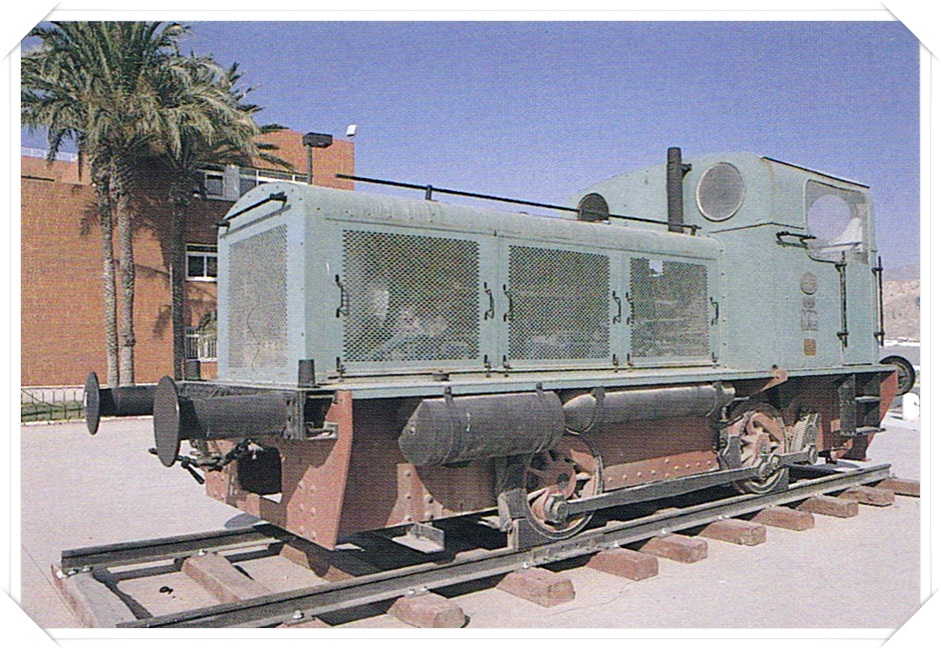

The first diesels to arrive were the Deutz Nos. 1 and 2 for the Port Authority Council. These were purchased n 1929 and put into service the following year. No 2 has been restored and stands in the port area near the Cable Ingles.

When the bridges and viaducts were strengthened, heavier and stronger locomotives began to appear. There was the 321 series, the versatile 333 and the renovated 1,900 that often towed the Almería - Madrid express. There was also the veteran (35 years in active service) 352 Talgo with a single cabin and its own passenger compartments. Finally there were the shunting engines type 10,101 10,300 and 10,700 completing the fleet.

The last diesel on the line was the famous Alco 1,300 of RENFE. It was designed specifically for hauling mineral traffic between Alquife, Marquesado and Almería and gave sterling service for more than 25 years. With the capability of linking up to four engines, the low weight per axle and strong brakes, it was ideal for the job.

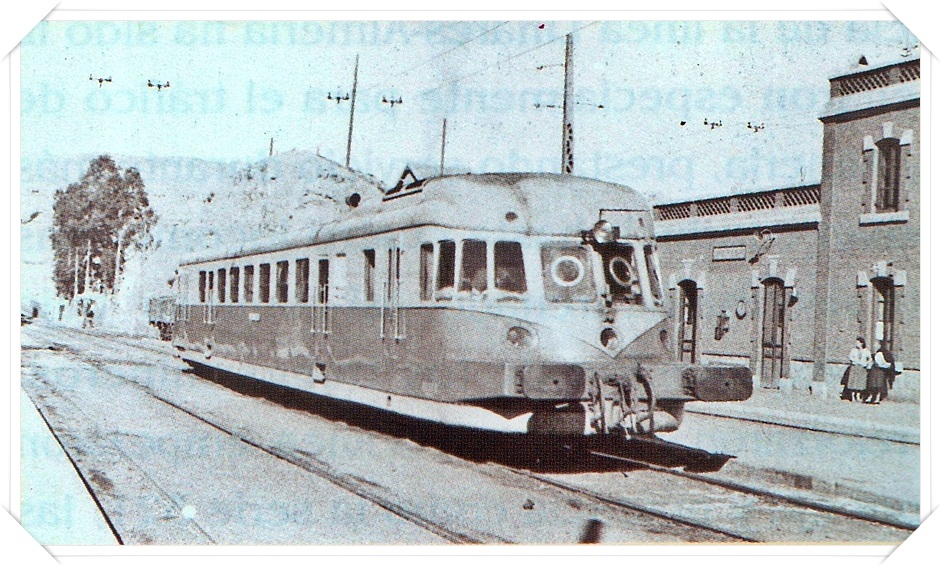

Older people will surely recall the arrival of the TAF Automotor in the 1950's. Their publicity claimed a top speed of 120 km/hr, and it was air-conditioned. The Ferrobus from Renault was more modest and was used to go to Granada and Linares-Baza. The so-called "camels" or "pushers" replaced them in the 1980's. These in turn gave way to the modem TRD (Regional Diesel Trains) and the renovated light trains. The Madrid route used the Italian TER Automotor before being superseded by the TALGO III.

7. Coaches and Wagons

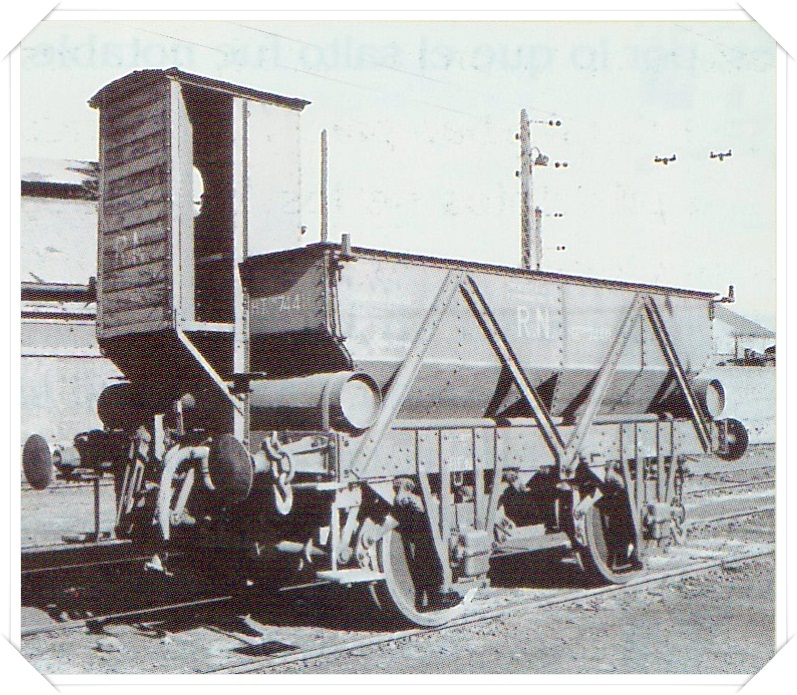

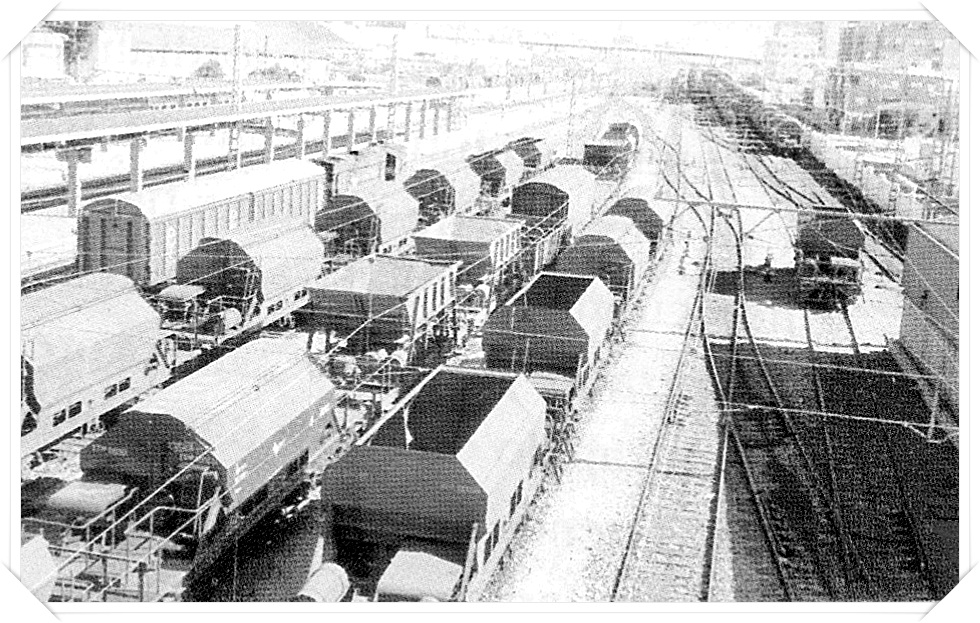

The line was essentially there for mineral transport, so mineral wagons were the most numerous. The early wagons were very simple and carried no more than 12-15 metric tons. They had two axles, sides and a hopper and chute so that mineral could be fed by gravity to the loading bay in Almería.

These evolved from a simple system whereby an operator on each wagon pulled a lever or turned a handle to engage the brake, to an air-brake system controlled from the engine. The loading capacity steadily increased to the present 56 metric tons. For other types of merchandise there were covered wagons; caged for livestock; tanks; platform and cranes. All improved as time passed.

The Almerian Company Francisco Oliveras SA was heavily involved with the railway. They constructed and repaired wagons of all types.

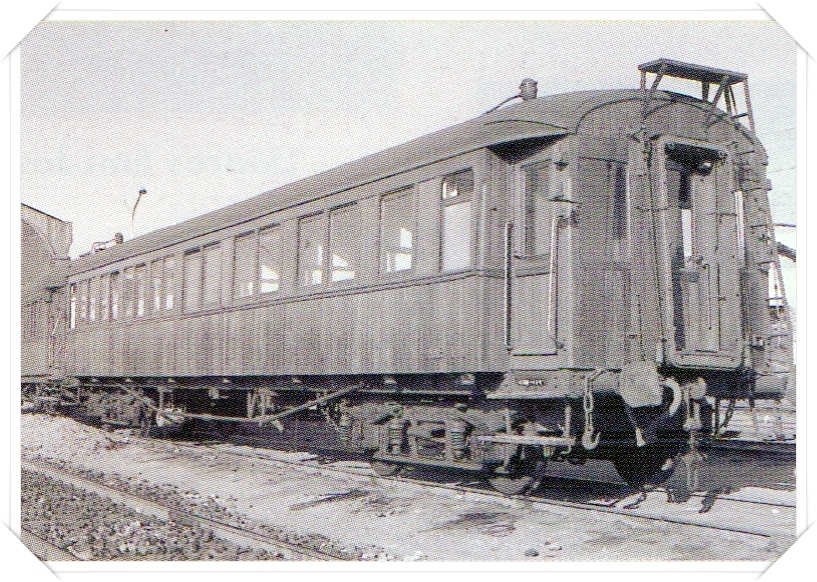

The SSRC had coaches (called passenger vehicles) of lst, 2nd and 3rd class, mixed, saloon coaches for directors of the company, wages coaches for staff; and vans for equipment and small goods. They had two axles with no communicating corridor; access to each compartment was by an external door. The exception was in lst Class, which had a side corridor. Originally they were heated by hot water under the seats but this was replaced by steam. Things improved when the Andalusia Railway took over. They bought coaches with bogies and with coach intercommunication through bellows, which required a bit of a leap for passengers!

In addition to other rolling stock from different companies coming on to the line, RENFE undertook the modernisation of the fleet from the 3,000 series with old metal coaches on to the important renovation of the marque to series 5,000 6,000 and 8,000 to the latest generations 9,000 and 10,000 with air conditioning and a central aisle. In the 1980s the Talgo III arrived, an important step forward in comfort, speed and efficiency.

For more pictures, go to the coaches and wagons section

8. Passenger Trains

When the line was completed, passenger trains were divided into two sections. The upper had mixed passenger-mail between Baza junction and Quereda and vice-versa. The lower had various trains in both directions between Almería, Guadix and Moreda. There were also trains between both sections with hair-raising journey times compared with today - around 11 hours.

There were mail trains, mixed goods trains and lst, 2nd and 3rd class expresses, which only stopped at certain stations.

With the improvements on the line came an increase in platforms at many stations. Transfers at Guadix and Moreda could be made. This improved many services including ones to Madrid. These had comfortable seats and beds as in the "Cortos" like the famous "Corto de Santa Fe".

At the beginning of the 1920's the general conditions for travellers were painful. There were old coaches discarded by other companies, without conveniences or lights and an awful swaying motion. The timekeeping was appalling and the traveller suffered a real torture. Things only got slowly better after nationalisation. From the 1950's modern Automotors TAF to Granada were put into service. In 1960 the TER gave a leap forward in quality and speed although it was still necessary to change at Moreda for Madrid with a time of 9 1/2 hours, or at Guadix for Barcelona. This trip, when there was work in Catalonia, involved more than 24 hours of rattling.

The noisy Ferrobuses linked with Linares, Baza and Granada in the 1970's. Surely everyone remembers the journeys on seats of “Skay” (a sort of fake leather) and the curtain separating the driver from his passengers.

By the 1980's the Talgo III seemed to bring us absolute modernity. Although other parts of Spain had tilting trains, little by little we got better regional services, night expresses with climate control.However, there was little actual improvement in journey times for long distance travel over previous years.

9. The Human Factor

By Manuel Alameda Delgado, Retired driver for RENFE

My life has always been linked to the railway. I am son, brother and father to railway workers. Many afternoons when I go for a walk I finish at the railway station.

My father, Manuel Alameda Parras, arrived from Los Villares (Jaen) during the early years of Almería railways and in 1911 he was working on the three-phase motors at Santa Fe. He was a driver and settled in that town. He married Presentación Delgado and had seven children.

Two were male and five female. The two males both became drivers, the youngest being me. I was born on 20th September 1920 next to Santa Fe station, with its smell of smoke and the sound of the telegraph. There I grew up listening to the hiss of the engines and the noise of the trains as they passed over the metal bridge.

Of my father's work I remember his journeys and his times away. We lived fairly well, he earned 15 pesetas per day. To me as a child, it was pleasurable to spend afternoons at the station learning Morse.

There were also difficult times. After the war, in 1939 I joined as a casual worker with the Andalusia Company, based in Almería. Here I was employed on ways and works. Between 1946 and 1951 I was sent to Guadix in the breakdown wagon. Here I learnt to manage the breakdown workshop. I worked with drills, laths and the forge. I learnt all the skills necessary to repair locomotives. It was hard and dedicated work which needed precision. I became a real master.

In the first months of 1951 I was moved to Santa Fe and in a few weeks I started provisionally as a driver's assistant. I started to drive the 3-phase engines just like my father. I have a permanent record of this time in the form of a scar on my left arm from an electrical burn. They were very durable and reliable engines. After this came the Secherons for a short while. I was promoted to driver on the new diesels. These were the American Alco engines that had a long life on the line.

The days then were long. We spent many hours away from home, in the cab. We cooked our meals in a battery powered oven. With long cold nights and terrible days of asphyxiating heat, these long mineral trains wound their way up the steep slopes of the line.

After forty-three years of service I retired with a clean record in September 1982. I saw many trains, lived through much change and witnessed a few accidents.

Now I have a son - Manuel Alameda León - who is head driver at Almería reserve and another - José Luis who was also a railwayman but had to retire due to an accident.

My father, my sons and I have completed one hundred years of railway life on the Linares- Almería line. If only my grandchildren and their descendants could cover the next one hundred years!

10. The Future

The book concludes with a look into the future. It highlights the poor service existing (in 1999) and asks how Almería can develop with such a poor service. It then lists what it sees as the essential improvements necessary for the Almerian Railway Network.

I show these below with, as far as I know, what changes have been made in the last 12 years. My comments are in italics.

* 1. Single track electrified line to Granada and Seville with connections to Madrid.

There are some more modern trains in service but as far as I am aware no significant change of service has been made to the line. Almería now has an Intermodal (bus and train combined) station. The old station is still derelict and shows signs of neglect. To be honest, with the very extensive motorway network that Almería now possesses, I do not see much more investment other than the AVE mentioned below.

* 2. Re-opening of the Guadix to Almendricos line (the old GSSR)

Not a chance! Many bits have now been built over or used for other purposes, such as Via Verdes (green footpaths) or as tracks for a water pipe.

* 3. A high-speed link to the north

This IS happening. The Almeria to Murcia AVE (High Speed) railway is under construction and should be operational in about 3-4 years.

* 4. Use of old lines as tourist routes.

Again quite a lot has happened. There are Via Verdes in Lucainena, Agua Amarga, Fines and Serón. Many of the old GSSR stations have been re-used as restaurants or workshops. The offices of Las Menas mines are now a hotel/restaurant and the mines are a tourist attraction. El Cable Ingles has been partly restored although the link line has now been severed.

A Todo Tren Appendix (August 2012)

The world financial crisis which started a few years ago is having a serious effect on Spanish plans for a nationwide high-speed network. The so-called “Mediterranean Corridor” linking France with Andalusia has essentially run out of funds. History is repeating itself. Edmund Sykes Hett and his Victorian entrepreneurs had similar ideas when they proposed the Great Southern of Spain Railway. They also ran out of money and had to content themselves with a much shorter line.

My interest is centred on the Murcia and Almería sections and I have been watching with interest the progress of these works (see the GSSR Update page). It was originally expected that the line would be completed next year but this is not certain. I understand that existing contracts will be completed but no more. Thus the line between Murcia and Almería will be completed, possibly by the end of next year. However, the final section from Nijar into Almería is now expected to link up with the existing line, rather than taking separate route.

This is interesting because the existing line is Spanish gauge whereas the new line is international gauge. So a third rail will have to be added to accommodate both systems. With similar constraints, the proposals for an Underground system in Almería (which would ease the appalling congestion in the city) are very much under threat. The President of ASAFAL, Don Jésus Martinez Capel has proposed a partial solution with just one line being built.

Another organisation, Ferrmed is proposing a re-opening of the old GSSR line. I do not see the slightest chance of this. What is Ferrmed? It is a Europe-wide organisation that met recently in Brussels. Below is the mission statement from their web site.

“FERRMED is a non-profit association that was officially founded and registered in Brussels on the 5th of August 2004. It is a multi-sectoral association that came out of the initiative from the private sector in order to enhance the European competitiveness by promoting the so called “FERRMED Standards”, the improvement of Ports and Airports connections with their respective hinterlands, the conception of Great Rail Freight Axis Scandinavia-Rhine-Rhone-Western Mediterranean, and a more sustainable development through the reduction of pollution and climate change emissions.”

A correspondant, Paul Larkin points out that; Your update mentions completion of the Almeria to Murcia section albeit with the link to the existing Spanish guage line close to Almeria. However, as I mentioned in my last e-mail, there are no obvious signs of work north of Turre and whilst the Sorbas tunnel is probably the biggest challenge on the line, Vera to Murcia must be the best part of 100 miles so will need some time to build including stations at Vera and Lorca.

Finally, from construction to destruction. The huge triangular building next to Almeria Station (known locally as the Toblerone) and used in the export of iron ore from El Cable Ingles, is under threat of demolition. Also the line that led from the station to the top of El Cable Ingles has now been cut so any chance of a tourist line to the top (admittedly faint) has gone. As is so often the case, Industrial Heritage is a poor second to business.

DLG 2012 with thanks to Antonio Aguilera and Gerald Strowbridge for their help.

Don Gaunt

April 2012

Gallery of Pictures. Hover over the pictures to enlarge them.

Part 1, Construction Work

Part 2, The Mines

Part 3, Locomotives

Part 4, Wagons and Coaches

©Copyright Don Gaunt, Antonio Aguilera and Domingo Cuéllar

Click here to go to the Faydon.com Home Page